Brow of a God / Jaw of a Devil

Brow of a God / Jaw of a Devil

Unsettling the Source of the Nile

Conceived in collaboration with Alexis Rider

Like a river that has ebbed, flowed, and redirected its path over millennia, archival sources are curious and complex. They are palimpsests of stories, libraries of time and their narratives are often disturbed by outside forces.

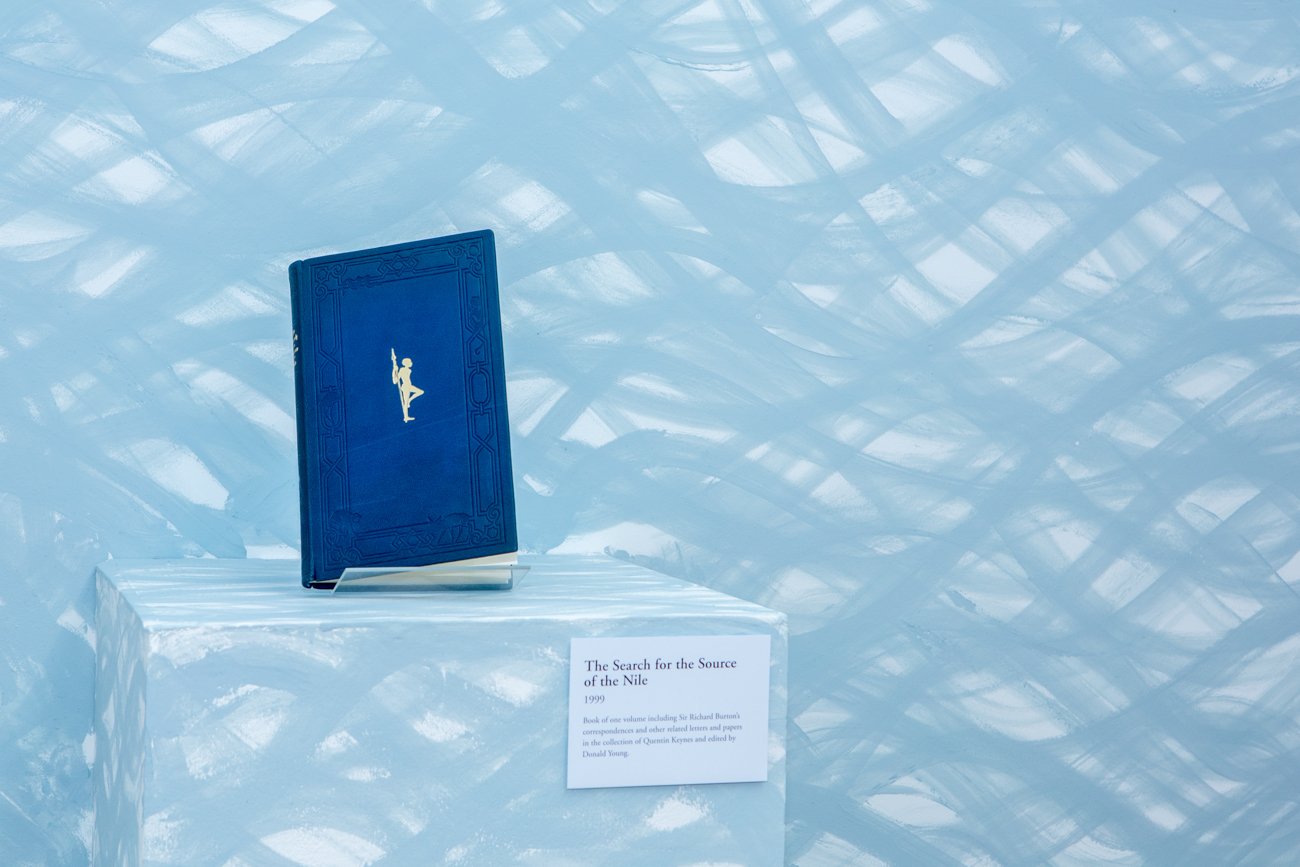

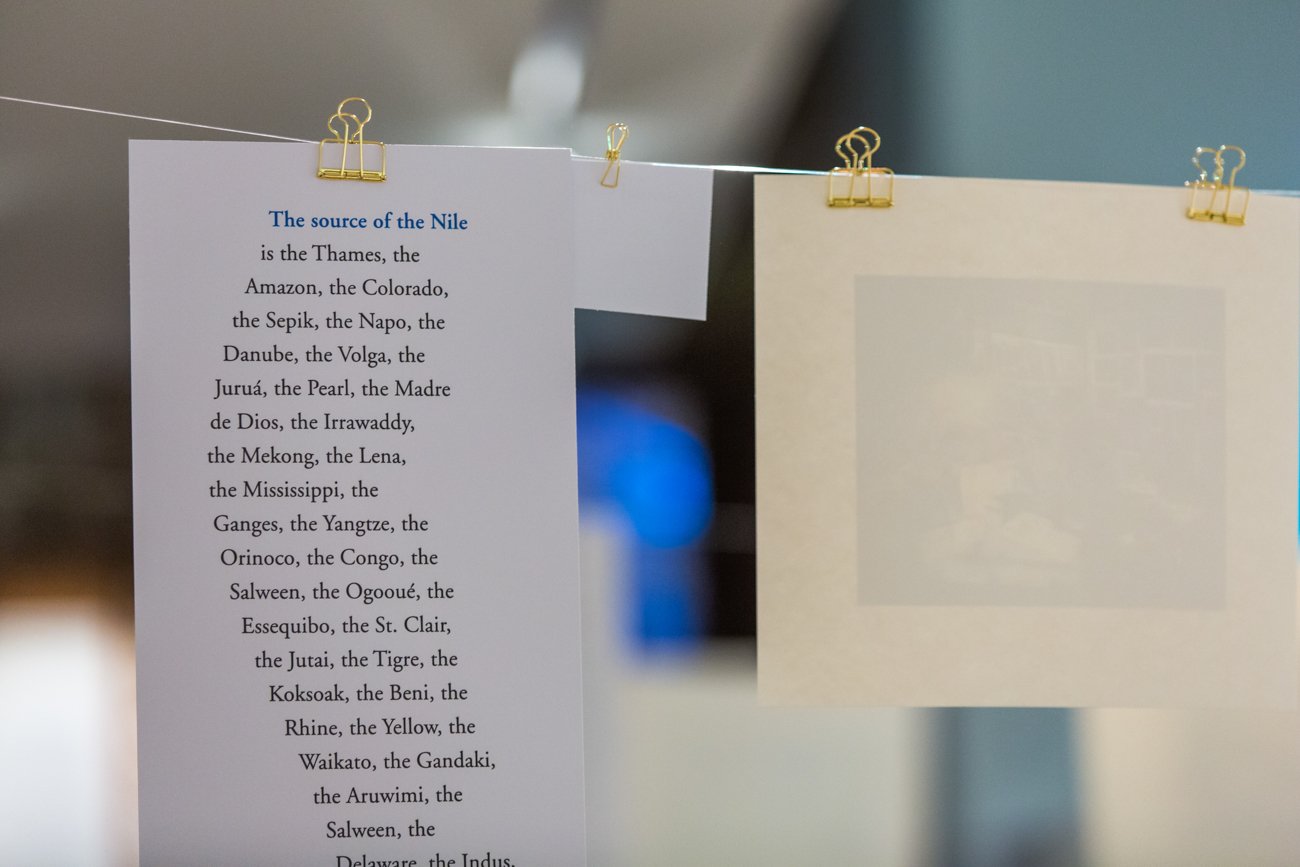

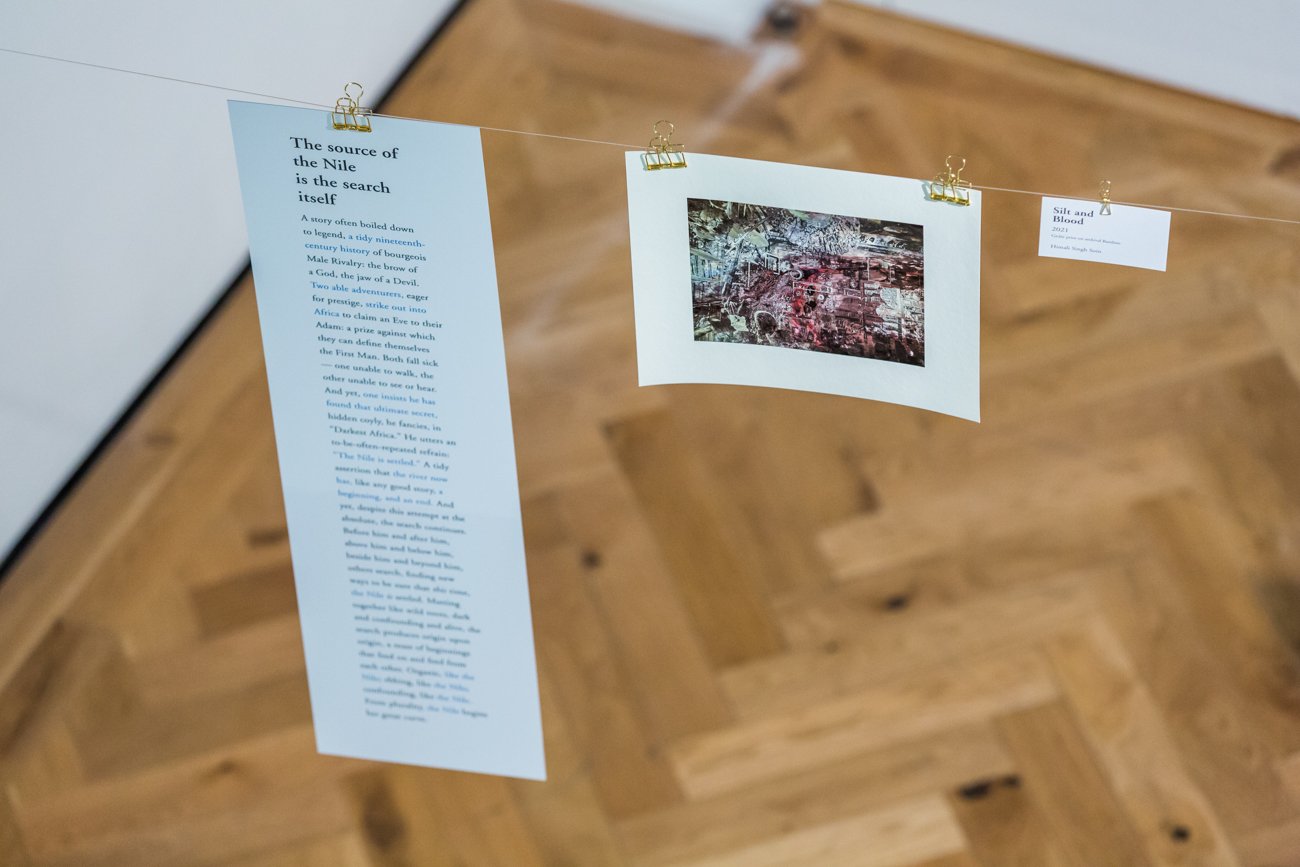

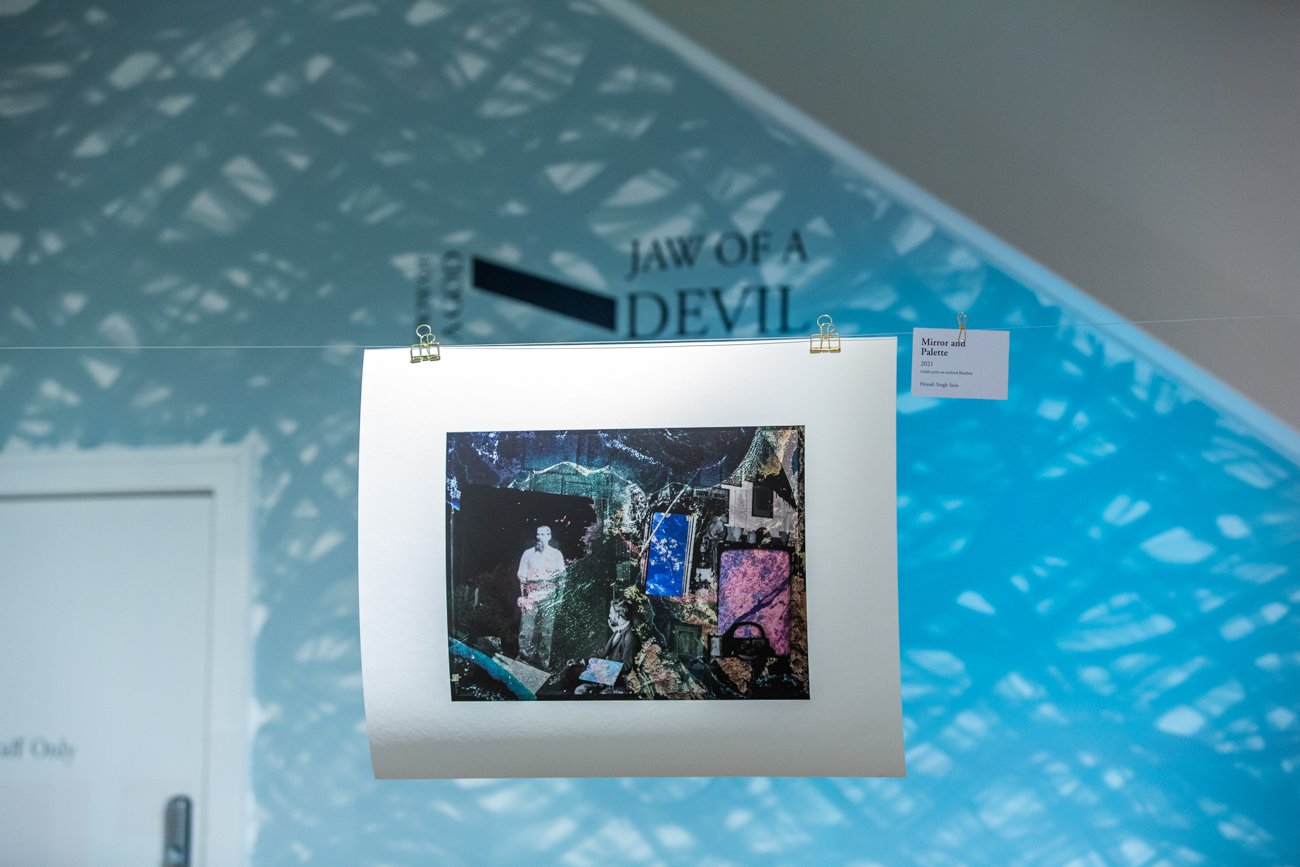

Brow of a God / Jaw of a Devil activates the archive of Richard Burton (1821-1890), a colonial explorer who is remembered most vividly for his search for the source of the Nile river and whose papers and memoirs were burnt by his wife at his deathbed. Superimposing silver prints of his own archives with contemporary imagery of the Nile, alongside a textual history of the many sources of the river, the exhibition creates an atmosphere of elusive, fluvial mystery, inviting the viewer to think of knowledge like a river: fluid, messy, feminine and enigmatic. Where is the centre? How do we attribute value? What occurs at the periphery? Who has been erased? Can we turn an absence into a presence? A shadow into a ghost? How do our minds shift when we change our axis of observation? By realigning narratives of the past, we might shift our visions of the future.

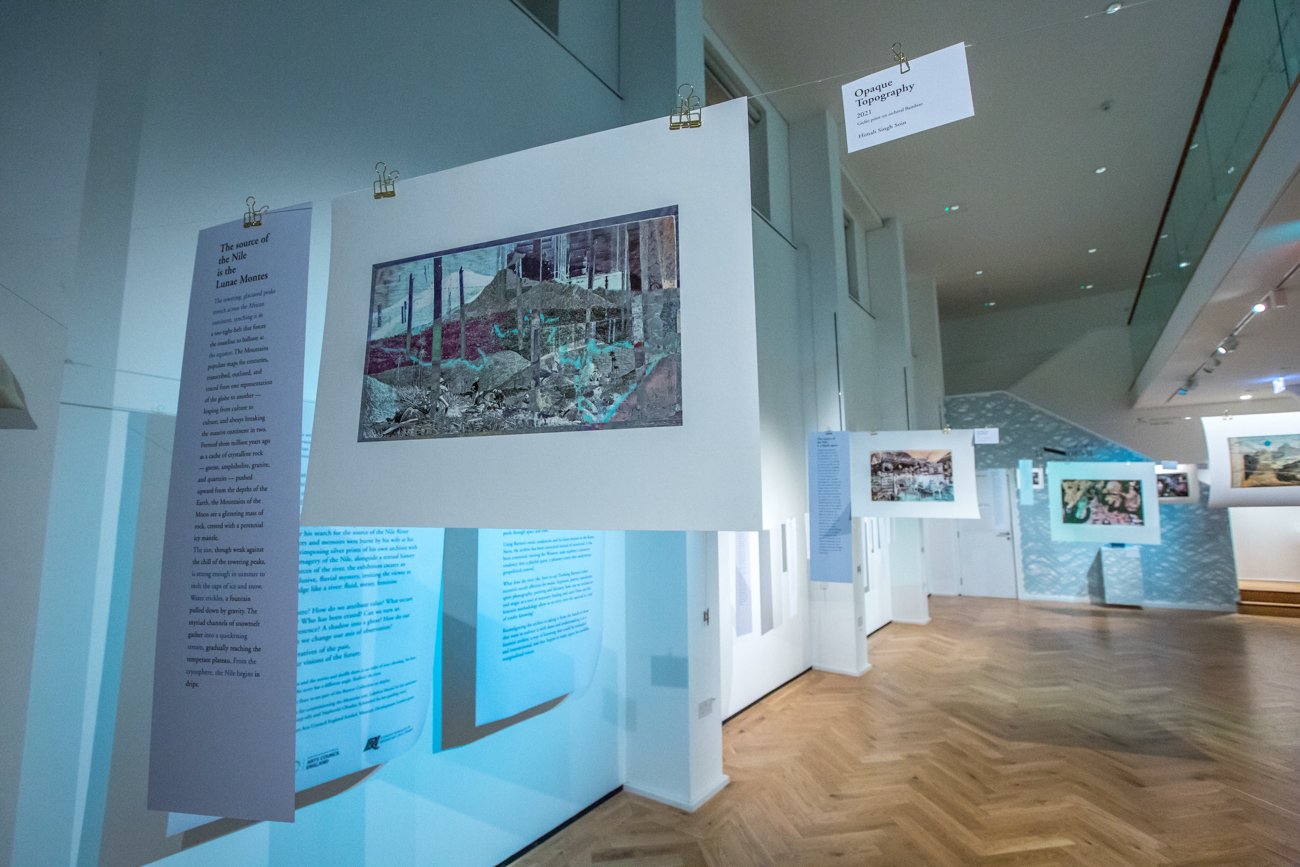

Brow of a God / Jaw of a Devil offers environmental phenomena as potential agents of decoloniality. Some are material and existent, like the Sudd: a dense vegetation that grows on the Nile, granting it the right to opacity from those that try to exploit it. Some are elusive and spectral, like the Mountains of the Moon: a range of mountains that was believed to tower over Africa, hiding the source of the Nile within them. While keenly aware that landscapes cannot speak for those lives that were undone by colonization, Brow of a God / Jaw of a Devil asks viewers to consider a world in which alternate narrators shape the flow of history, and where power diffuses and pools through space and time.

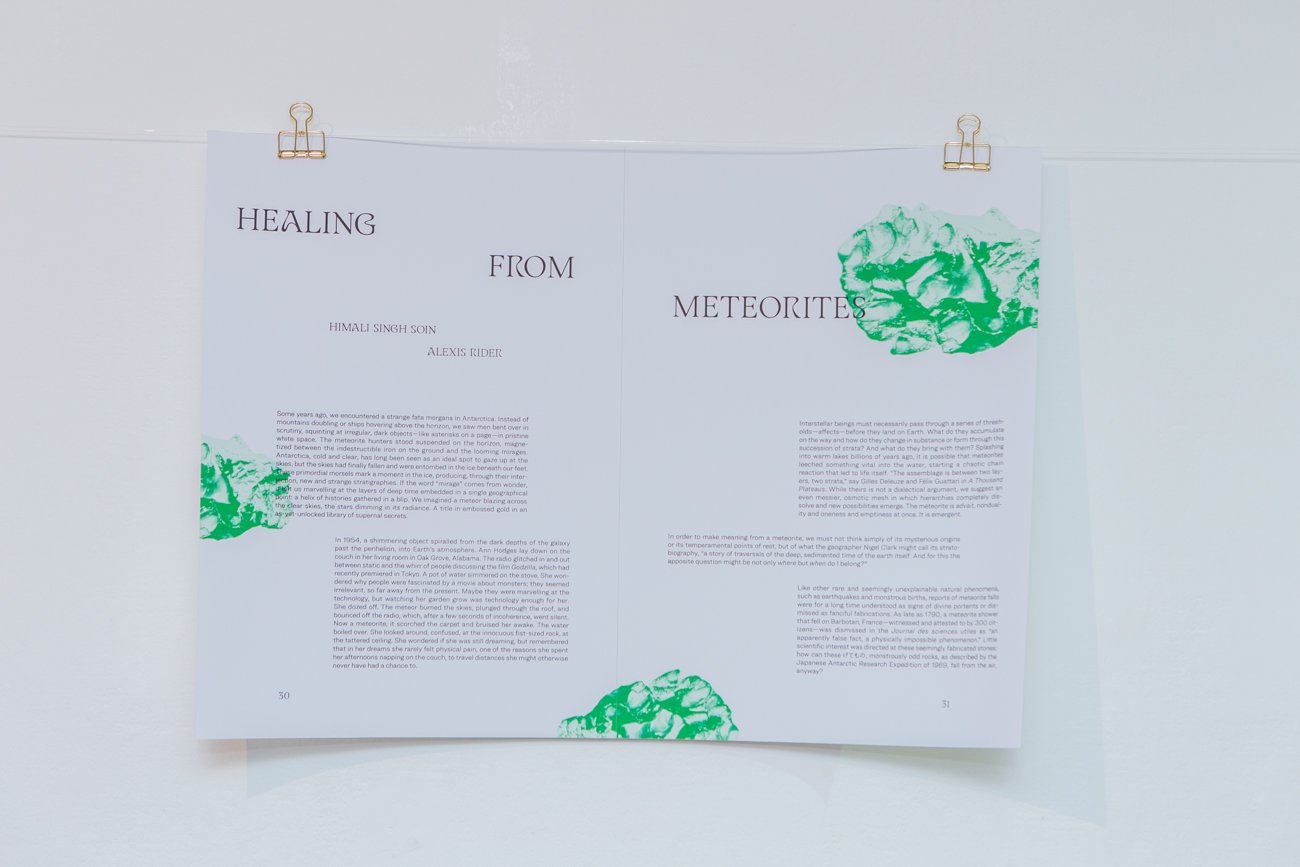

Using Burton’s erotic tendencies and his keen interest in the Kama Sutra, the archive has been eroticized instead of exoticized. It has been contorted, turning the Western, male explorer’s extractive tendency into a playful quest, a pleasure centre that undermines geopolitical control. What does the river, she, have to say? Evoking Burton’s other eccentric occult affinities for music, hypnosis, poetry, translation, spirit photography, painting and falconry, how can we reclaim art and magic as a tool of necessary healing and care? How can this feminist methodology allow us an entry into the spectral as a way of tender knowing? Reconfiguring the archive is taking it from the hands of those that want to redirect it with dams and understanding it as a feminist archive, a way of knowing that could be embodied and intersectional; and that begins to make space for erased, marginalized voices.